This project interviewed recent immigrants to the community, exploring their perceptions of New York prior to arrival, the media images that shaped their views of the city, their experiences since arriving, and their expectations for the future.

Understanding the Migratory Crisis: An Oral History of New Migrants in Lower Manhattan

Immigration is a complex and often contentious issue deeply intertwined with historical and contemporary media portrayals. The perspectives of immigrants and the host society on immigration are heavily influenced by the narratives presented through the media. Typically, one side may view immigration with a critical or even catastrophic lens, while the other might see the destination country in an idealized light. Once in the United States, some migrants internalize the negative representation of immigration and, while seeing themselves as the exception, start to favor closing the door behind them.

This oral history project interviewed fourteen migrants and asylum seekers, under the condition of anonymity, who arrived in New York City within the last two years. The interviews were conducted in the winter and spring 2023–2024 at the New Amsterdam Library. The interviewed asylum seekers were from Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela and the Dominican Republic, and included people from a wide range of experiences, classes, occupational and educational backgrounds, which questions the term migrant as a stable or all-encompassing category. Most of them entered the United States through the southern border, except for two who flew here. The border ports of entry included Eagle Pass and El Paso, Texas, and Calexico and San Ysidro, California.

Based on the testimonies, the primary contributing factors to the current migration crisis are a decline in safety in many Latin American nations and post-pandemic economic crises. After the pandemic, a migratory exodus across the world was an expected development, the fact that this has caught many by surprise, including government officials and the media, is difficult to explain. The advent of social media has had an obvious impact on immigration flows, but it has mainly amplified communication and information networks between diasporas that already existed through word of mouth. For this exhibition, we extracted some fragments from the most compelling interviews.

Immigration is a complex and often contentious issue deeply intertwined with historical and contemporary media portrayals. The perspectives of immigrants and the host society on immigration are heavily influenced by the narratives presented through the media. Typically, one side may view immigration with a critical or even catastrophic lens, while the other might see the destination country in an idealized light. Once in the United States, some migrants internalize the negative representation of immigration and, while seeing themselves as the exception, start to favor closing the door behind them.

This oral history project interviewed fourteen migrants and asylum seekers, under the condition of anonymity, who arrived in New York City within the last two years. The interviews were conducted in the winter and spring 2023–2024 at the New Amsterdam Library. The interviewed asylum seekers were from Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela and the Dominican Republic, and included people from a wide range of experiences, classes, occupational and educational backgrounds, which questions the term migrant as a stable or all-encompassing category. Most of them entered the United States through the southern border, except for two who flew here. The border ports of entry included Eagle Pass and El Paso, Texas, and Calexico and San Ysidro, California.

Based on the testimonies, the primary contributing factors to the current migration crisis are a decline in safety in many Latin American nations and post-pandemic economic crises. After the pandemic, a migratory exodus across the world was an expected development, the fact that this has caught many by surprise, including government officials and the media, is difficult to explain. The advent of social media has had an obvious impact on immigration flows, but it has mainly amplified communication and information networks between diasporas that already existed through word of mouth. For this exhibition, we extracted some fragments from the most compelling interviews.

Origins

Interview 2:

“I come from Ecuador, from an indigenous province of Cotopaxi. In my country, indigenous people are very discriminated against. We have been rejected by the government for a long time. We have had a lot of violations of our rights, such as health, education, and the...price of the products we produced. So...as the daughter of one of the leaders of ten indigenous communities in the province of Cotopaxi, I made the decision to get out of there because we have been mistreated.”

Interview 5:

“I'm from Guayaquil...I was born and lived there and what was there was ugly. My husband wanted to kill himself...and so I came leaving my children behind. That worries me and I would like to bring them to me, or what can I do...it's just that it's a sad thing. It's not easy...but I flew to Nicaragua, but on my own I came anyway; I arrived here thank God.”

Interview 10:

“I had a situation at work. I was transferred to a red zone in Colombia where there were armed groups outside the law. These armed groups began to feel a little intimidated by all the work that was being done by my company and many of the employees began to receive threats to intimidate us and get us out of the city...I decided to take a whirlwind trip to New York to try to calm things down. When I tried to return to Colombia, no, it was not possible...there was a constant threat. So I preferred to stay here.”

Interview 11:

“I was a victim of sexual abuse by a well-known person in the LGBT camp in the city, in the capital Bogotá, in Colombia...After the sexual abuse, I spent several months sick and started researching the topic of treating diseases here in the United States because health care is much more advanced...at the time of the sexual abuse, the person was a carrier of HIV, so he transferred the virus to me. Since then I have had a fairly strong health decline. We do not have the same possibilities with healthcare in Colombia as there is in the United States.”

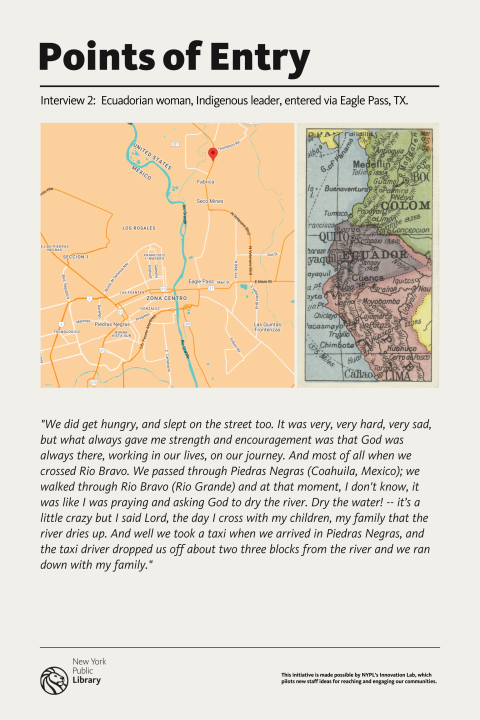

Points of Entry

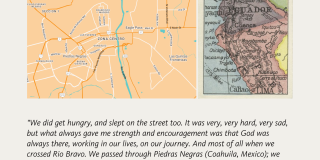

"We did get hungry, and slept on the street too. It was very, very hard, very sad, but what always gave me strength and encouragement was that God was always there, working in our lives, on our journey. And most of all when we crossed Rio Bravo. We passed through Piedras Negras (Coahuila, Mexico); we walked through Rio Bravo (Rio Grande) and at that moment, I don't know, it was like I was praying and asking God to dry the river. Dry the water! -- it’s a little crazy but I said Lord, the day I cross with my children, my family that the river dries up. And well we took a taxi when we arrived in Piedras Negras, and the taxi driver dropped us off about two three blocks from the river and we ran down with my family."

Interview 2: Ecuadorian woman, Indigenous leader, entered via Eagle Pass, TX

"We did get hungry, and slept on the street too. It was very, very hard, very sad, but what always gave me strength and encouragement was that God was always there, working in our lives, on our journey. And most of all when we crossed Rio Bravo. We passed through Piedras Negras (Coahuila, Mexico); we walked through Rio Bravo (Rio Grande) and at that moment, I don't know, it was like I was praying and asking God to dry the river. Dry the water! -- it’s a little crazy but I said Lord, the day I cross with my children, my family that the river dries up. And well we took a taxi when we arrived in Piedras Negras, and the taxi driver dropped us off about two three blocks from the river and we ran down with my family."

Trekking the Jungle

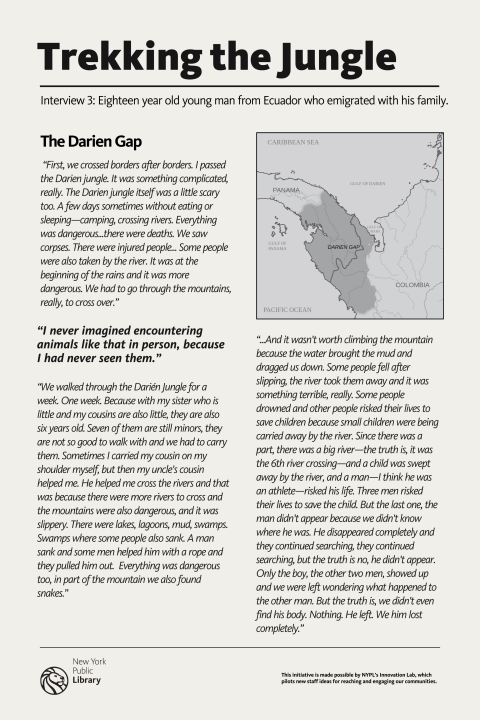

“First, we crossed borders after borders. I passed the Darien jungle. It was something complicated, really. The Darien jungle itself was a little scary too. A few days sometimes without eating or sleeping—camping, crossing rivers. Everything was dangerous...there were deaths. We saw corpses. There were injured people... Some people were also taken by the river. It was at the beginning of the rains and it was more dangerous. We had to go through the mountains, really, to cross over.”

Interview 3: Eighteen year old young man from Ecuador who emigrated with his family.

The Darien Gap

“First, we crossed borders after borders. I passed the Darien jungle. It was something complicated, really. The Darien jungle itself was a little scary too. A few days sometimes without eating or sleeping—camping, crossing rivers. Everything was dangerous...there were deaths. We saw corpses. There were injured people... Some people were also taken by the river. It was at the beginning of the rains and it was more dangerous. We had to go through the mountains, really, to cross over.”

“I never imagined encountering animals like that in person, because I had never seen them.”

“We walked through the Darién Jungle for a week. One week. Because with my sister who is little and my cousins are also little, they are also six years old. Seven of them are still minors, they are not so good to walk with and we had to carry them. Sometimes I carried my cousin on my shoulder myself, but then my uncle's cousin helped me. He helped me cross the rivers and that was because there were more rivers to cross and the mountains were also dangerous, and it was slippery. There were lakes, lagoons, mud, swamps. Swamps where some people also sank. A man sank and some men helped him with a rope and they pulled him out. Everything was dangerous too, in part of the mountain we also found snakes.”

“...And it wasn't worth climbing the mountain because the water brought the mud and dragged us down. Some people fell after slipping, the river took them away and it was something terrible, really. Some people drowned and other people risked their lives to save children because small children were being carried away by the river. Since there was a part, there was a big river—the truth is, it was the 6th river crossing—and a child was swept away by the river, and a man—I think he was an athlete—risked his life. Three men risked their lives to save the child. But the last one, the man didn't appear because we didn't know where he was. He disappeared completely and they continued searching, they continued searching, but the truth is no, he didn't appear. Only the boy, the other two men, showed up and we were left wondering what happened to the other man. But the truth is, we didn't even find his body. Nothing. He left. We him lost completely.”

Twice Displaced

Interview 4: Colombian wife and mother, arrived via Calexico, CA.

Fleeing Violence

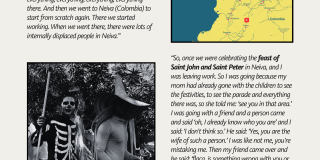

“We had to leave immediately, that is, they [paramilitaries] gave us eight hours to leave the place, and I said, ”which eight hours? We're leaving now!” And my husband told me Ok. We went out, left, alone. We took what we could, the clothes, half of what we had, and we left everything, everything, everything, everything there. And then we went to Neiva (Colombia) to start from scratch again. There we started working. When we went there, there were lots of internally displaced people in Neiva.”

“So, once we were celebrating the feast of Saint John and Saint Peter in Neiva, and I was leaving work. So I was going because my mom had already gone with the children to see the festivities, to see the parade and everything there was, so she told me: ‘see you in that area.’ I was going with a friend and a person came and said ‘oh, I already know who you are’ and I said: ‘I don't think so.’ He said: ‘Yes, you are the wife of such a person.’ I was like not me, you're mistaking me. Then my friend came over and he said: ‘flaca, is something wrong with you or is that man bothering you?’ I said: ‘no, don't worry,’ but I was nervous, so they found me. I didn't go out anymore, I didn't go out like that anymore. I put on sunglasses and a hat every time I went out. I went out, but I was left with that uncertainty.”

To New York City Via Calexico & Houston

Interview 4: Colombian wife and mother, arrived via Calexico, CA.

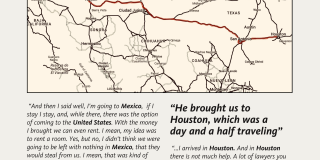

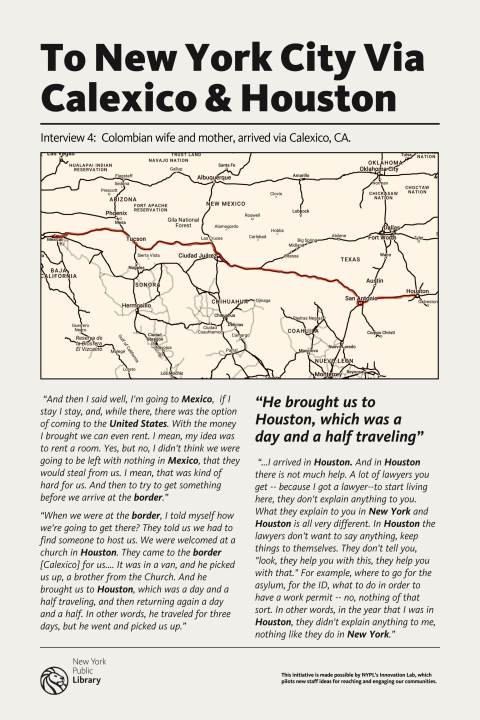

“And then I said well, I'm going to Mexico, if I stay I stay, and, while there, there was the option of coming to the United States. With the money I brought we can even rent. I mean, my idea was to rent a room. Yes, but no, I didn't think we were going to be left with nothing in Mexico, that they would steal from us. I mean, that was kind of hard for us. And then to try to get something before we arrive at the border.”

“When we were at the border, I told myself how we're going to get there? They told us we had to find someone to host us. We were welcomed at a church in Houston. They came to the border [Calexico] for us.... It was in a van, and he picked us up, a brother from the Church. And he brought us to Houston, which was a day and a half traveling, and then returning again a day and a half. In other words, he traveled for three days, but he went and picked us up.”

“...I arrived in Houston. And in Houston there is not much help. A lot of lawyers you get -- because I got a lawyer--to start living here, they don't explain anything to you. What they explain to you in New York and Houston is all very different. In Houston the lawyers don't want to say anything, keep things to themselves. They don't tell you, "look, they help you with this, they help you with that." For example, where to go for the asylum, for the ID, what to do in order to have a work permit -- no, nothing of that sort. In other words, in the year that I was in Houston, they didn't explain anything to me, nothing like they do in New York.”

Reaching the Southern Border

Interview 5 : Ecuadorian woman, fleeing domestic violence, arrived via Lukeville, AZ.

Entering Through the Sonoran Desert: Sonoyta, Sonora

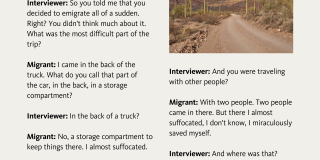

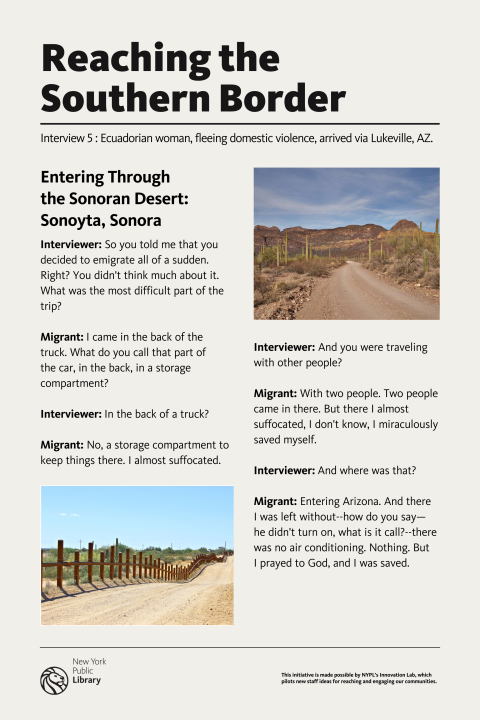

Interviewer: So you told me that you decided to emigrate all of a sudden. Right? You didn't think much about it. What was the most difficult part of the trip?

Migrant: I came in the back of the truck. What do you call that part of the car, in the back, in a storage compartment?

Interviewer: In the back of a truck?

Migrant: No, a storage compartment to keep things there. I almost suffocated.

Interviewer: And you were traveling with other people?

Migrant: With two people. Two people came in there. But there I almost suffocated, I don't know, I miraculously saved myself.

Interviewer: And where was that?

Migrant: Entering Arizona. And there I was left without—how do you say—he didn't turn on, what is it call?—there was no air conditioning. Nothing. But I prayed to God, and I was saved.

Why New York?

Interview 10: Colombian woman, energy professional, arrived via JFK.

“...I really like New York. In another life I must have been a New Yorker. I like this city. I don't know, eh. Let's say that maybe Bogotá is also a cosmopolitan city that moves quite a lot, so I feel very identified, I feel very comfortable.”

“I tried to move back to Bogotá, but the threats had already reached Bogotá. I didn't feel safe anymore, even staying with my family, and I decided to take a whirlwind trip to New York to try to calm things down. When I tried to return to Colombia, no, it was not possible because these threats were effective against many of my colleagues, and my work could no longer be recovered. I no longer got other job options. And because we were left with a reputation by these people, that we were not well regarded in the region, and that if anybody sees us then let them know. So, you have a frequent threat. Then, I preferred to stay here.”

“ I had planned to travel for tourism with my friend, but I had a situation at work. I was transferred to a red zone in Colombia where there were armed groups outside the law. These armed groups began to feel a little intimidated by all the work that was being done by my company and many of the employees began to receive threats to intimidate us and get us out of the city.

“...I feel that I learned to move around very quickly, that the city provides me with security, despite the fact that there are many cases of insecurity, many cases of attacks, many cases of many things. New York makes me feel safe, and I visited other cities where I traveled for tourism previously, I didn't like them. For the same reason, transport is very limited. Everything at 6 or 7 at night isn't working anymore and I'm not that kind of person. I like cosmopolitanism better.”

Social Media & Migration

Interview 11: Colombian LGBTQ activist, arrived via Hidalgo, TX

“Ok, initially for me, in my particular case, the TikTok network had a big impact, which I just mentioned, since there are many influencers who manage this communication channel who show their daily lives of what it's like to live and be an immigrant in different cities of the United States. I really didn't think that New York was going to be like my home base when I arrived, but, really, these social networks, TikTok and Facebook, helped me make the decision to get here, let's say, with more ideas and a little more confidence to be in a totally unknown country with a different language, with a totally different culture from where I come from in Latin America.”

“No, let's just say the information that I came with was more about the process of arriving, but not about being able to settle in New York. Although there are some, let's say, videos, or people on social networks who talk about the issue but don't give a lot information about how to look for—where to go, where to start. So that's difficult. That information is a little bit missing. They talk a lot about how to cross [the border], how to get here, what help to ask for initially, but on how to support yourself with employment, how to look for good housing, or what connections—very little information is provided on social networks.

“we see, in an interesting way, like an American dream, that it is possible, that people would find work anywhere, that the hiring signs were on every window looking for someone to work, and that in the first week you could already make a lot of money to send to your country, that within the first few months you were already becoming a millionaire. That was like the idealization that exists in Colombia or, for example, that I had in my country.”

Becoming an Exile

Interview 12: Venezuelan film set designer, entered via a humanitarian parole.

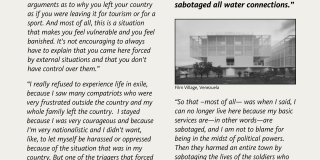

“I am originally from Venezuela. My country hit rock bottom economically and socially because of the international economic blockade and we had to be exiled against our will to seek new life opportunities in the countries closest to us. Well, it's a bit demoralizing to arrive here and have to deal with always having to give arguments as to why you left your country as if you were leaving it for tourism or for a sport. And most of all, this is a situation that makes you feel vulnerable and you feel banished. It's not encouraging to always have to explain that you came here forced by external situations and that you don't have control over them.”

“I really refused to experience life in exile, because I saw many compatriots who were very frustrated outside the country and my whole family left the country. I stayed because I was very courageous and because I'm very nationalistic and I didn't want, like, to let myself be harassed or oppressed because of the situation that was in my country. But one of the triggers that forced me to leave was after the dictatorship shut the water lines in my town, because I lived in near political authorities who rebelled against the dictatorship. So the government, in order to oppress them, sabotaged all water connections. I spent three months buying water, I couldn't keep buying water and I couldn't sell my property either because there was no water and no one was going to buy it for me because they sabotaged everything.

“So that –most of all— was when I said, I can no longer live here because my basic services are—in other words—are sabotaged, and I am not to blame for being in the midst of political powers. Then they harmed an entire town by sabotaging the lives of the soldiers who had rebelled against the dictatorship and the civilians who were there, who had not participated in a direct confrontation with the government, we were all harmed by those political rivalries. Then that made me feel very vulnerable and I realized that in reality I couldn't continue to be obstinate in staying where there was no longer a way to survive in a place like that. And that forced me to abandon everything and start from scratch here.”

Escaping the Smugglers

Interview 13: Dominican young man with a law degree.

In the Outskirts of Mexico City

“The most difficult thing about my trip was that for us, a lady who had not paid in Guatemala, had not deposited the full money with the coyotes, and she had three days left to deposit the money. Then they gave her a chance of two more days and they told her if they don't deposit the money, you are going neither back nor forward, we're going to send you with Santa Cruz or with San Pedro. They told her like that. The woman was crying. They didn't deposit her money, the woman was taken away from there, she didn't show up anymore. Then there were two more people who were going through the situation.”

“...at one point I can't identify if they were cops or what, but they were hooded in military uniform. But then, at one time I was brushing my teeth on the second level. Upstairs the house was destroyed. Like a window - it didn't have a window, it only had a hole. They got there, and when they arrived, a shootout broke out and I didn't think anything. I lost my phone, I lost my clothes. I threw myself from the second floor. I hurt my arm. Form there I crawled and woke up on the street in a dumpster. They saw me and they shot at me. I could hear the gunshots. But if I'm here it's like they say in my country, if you're here it's for an end, because God has a purpose. That wasn't your day. But I went through - I went through a lot of things, I had to sleep over on the street. I had to leave the next day at 5:00 am, walking. I had a hand watch and I guided myself with the watch, hour by hour. Asking around, I was able to get to the city center of D.F. That happened to me in Mexico.”

Additional Reading to Better Understand the Migratory Crisis

The Devil's Highway: a true story

By Luis Alberto Urrea 2004-2011

The End of the Myth: from the frontier to the border wall in the mind of America

By Greg Grandin 2019-2020

Everyone who is Gone is Here: the United States, Central America, and the making of a crisis

By Jonathan Blitzer 2024

Sponsors

This initiative is made possible by NYPL’s Innovation Lab, which pilots new staff ideas for reaching and engaging our communities.